I thought I would read this sort of autobiography by one of my favourite fictioneers and so far I am pleased to have done so.

Pages 3 – 70

“To your mind, there was no greater injustice than to be doubted when you had told the truth, to be called a liar when you hadn’t lied, for there was no recourse then, no way to defend your integrity in the face of your accuser, and the frustration caused by such a moral injury would burn deep into you, continue to burn into you, becoming a fire that could never be extinguished.”

Paul Auster is almost exactly my age and these are his memories from ignited consciousness onward, in a simple language but one that sometimes entails very long sentences, like Proust’s, but, so far, easily digestible and inspiring and conveying a life’s early years perfectly, the same period as my own early period in the 1950s, except his 1950s were America and mine England. He a Jew, me not. But I feel a kinship, a link, a Jungian synchronicity. He covers such disparate matters as the Lone Ranger and Tonto, the Polio epidemic, aeroplanes, his heroes, his thoughts, his disappointments, his joys….

TO BE CONTINUED IN THE COMMENT STREAM BELOW AS AND WHEN I READ THIS BOOK:

Pages 70 – 101

“What did this mean about the world? That everyone in it was more or less hidden, and because we were all other than what we appeared to be, it was next to impossible to know who everyone was. You wonder now if that sense of not knowing wasn’t responsible for making you so passionate about books — because the secrets of the characters who lived inside novels were always, in the end, made known.”

And the huge sentences as well as the short ones eat me up with relish as if I am the tastiest reader possible!

This section is when he crosses the seemingly vast convulsive aeons of, say, just two years between certain pre-teen ages – and I compare his imminent and almost immanent puberty and interest in girls with the emergence of his obsessive nature in reading books so as also to create the same imminence or immanence of writing books or simply to beat others to reading them, in some teacher’s silly competitive project. I, too, was once accused brutally of things of which I was innocent by a teacher when I was exactly at Auster’s then age. It has similarly marked me out, perhaps, causing me to mark out white paper, too, with the intrinsic emblems of fiction as truth? This is a Tale of Two Trophies, too, the one you keep or the one you give away. Like parts of yourself.

This first section of the book ends here, the one with a title that gives the whole book its overall title. I notice that the next section is entitled: ‘Two Blows To The Head’….

Ten years old – and a stunningly page-turning account of his seeing THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN cinema film. Either this is a boy’s sudden realisation of the shrinking nature of life itself or, more likely, the impetus for the then future international best-selling author to create fantasy to big himself up outside this book’s life story, outside its shuttling frames: that once foreseeably diminishing dream of self.

Whatever the reason for majoring upon this single event in the author’s life, it does provide an unforgettable reading experience for the reader, an experience comparable to the author’s own cinema experience that it actually describes.

Pages 132 – 174

“…by fourteen, fourteen and a half, immersing yourself in classical music. Bach and Beethoven, Handel and Mozart, Schubert and Haydn, drawing sustenance from those composers in ways that wouldn’t have seemed possible just a year or two before, discovering the music that has continued to sustain you through all the years that have followed.”

Shuttling frames, and fluttering calendar pages…

Another gap, no doubt, of short-yeared aeons between the shrinking man and the second ‘blow to the head’ which is in this section a rather slavish account by this autobiography’s subject, by this book’s ‘you’, of the film he watched when he was fourteen called ‘I Am A Fugitive from a Chain Gang’, a story of from hard luck to hard labour, via the alchemy of chance and fateful hamburgers. We actually WATCH this film detail by detail through the words on the page, a new experience of reading a film, within the context of a life: the life of the film and the life in the film.

Even with the leg chains removed, some still walk as if they are still wearing them. And the past making of this film that he watched in 1961 pre-dated, for this Jewish author, the death camps of the war…

.

.

Pages 177 – 239

“– write requiems for the living –“

We now begin ‘Time Capsule’…

Belongings never being fixtures, our Auster wishes he had kept a journal, but, fortuitously (?), an old flame copies to him today all the letters he wrote to her in the late 1960s when he was in his very early 20s…

“I think the closest man can come to the feeling of eternity is by living in the present…”

And we live fascinated through a choice of these letters’ quoted contents and his interpolations today: a life that had otherwise been lost. I am an even tastier reader now.

“It is the stranger who intrigues you, the floundering boy-man who writes letters…”

His aspirations, disappointments, naivety, creative writing, cinema ambitions, sometimes failing academic life, Viet Nam, French poetry, family, ‘Revisions’, his ‘Hand to Mouth’ existence, and that is serendipitous as I just reviewed someone else’s story with that exact same title and mentioned that I am a sucker for any fiction that uses ‘Tristram Shandy’ as a prop, as does this section of Auster’s autobiographical ‘fiction’…and in that same review I mentioned I was a sucker for Requiems…

“Now that they are no longer alive, you see no reason for them to remain anonymous. They are ghosts now, and the only thing that belongs to a ghost is his name.”

Pages 239 – 271

“In reading over the letters you wrote in leading up to that date (April 23), you are stunned by the depth of your unhappiness, shocked by how close you were to what sounds like absolute disintegration, for in the years that followed memory had blurred the details of that time, and you had somehow managed to soften the pain, to turn a full-blown inner crisis into a dull sort of malaise that you eventually put behind you.”

The ‘you’ there is Auster the Author.

The word ‘disintegration’ is important to me as it echoes the ‘integrity’ in the first quote above I made. This book tells me about many things, reflections, echoes, fellow feeling, admiration, pity, my own shame at forgetting parts of the past, but it also reminds me of the Proustian Selves that make up one’s integrity. An inviolable integrity, nevertheless.

This section includes a very long letter, a fascinating document, one that is so perfectly couched, one wonders if it has been fictionalised or improved or doctored by hindsight. But, no, nobody would reproduce this document unless it was true and exactly as it was originally written. Yet, one always can choose what documents or excerpts to reproduce, even if undoctored in themselves, so as to create the desired gestalt? But “a time capsule must never be tampered with” has been spotted in one of this section’s footnotes…

The book’s text ends with “Will you write to me soon?, Love, Paul.”

I hope the above will suffice. And I hope I am not seen to be ‘the fat sadist in the bumper car’.

“Years of floundering seem to be emerging into a strange & clumsy strength that knows no fears and each day finds connections between elements that are … outlandishly disparate. A methodical spontaneity. A dialectic that excludes nothing.”

Pages 274 – 341

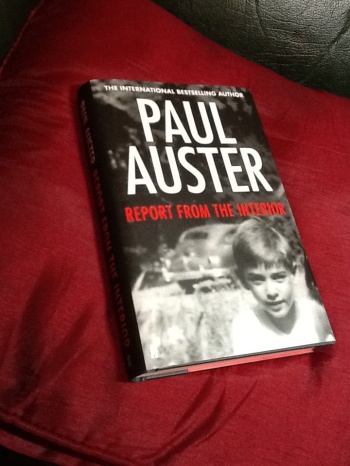

There follows a wonderful ‘Album’ of over 100 black and white photographs to accompany the text.

end