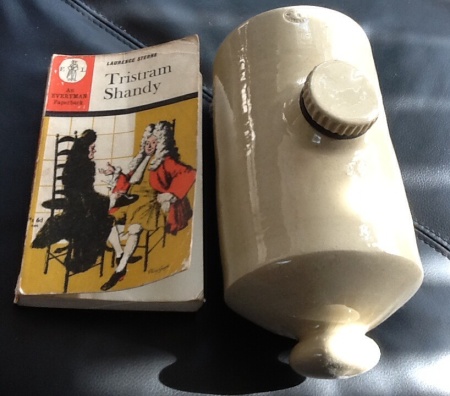

THE LIFE AND OPINIONS OF TRISTRAM SHANDY, GENT. (1759-1767) by Laurence Sterne

I first read this work in the 1960s and have not revisited it since then. I have an instinct it may be relevant to our modern age’s Internet-digressiveness, pessimism, melancholy, Ligottian Anti-Natalism &c. &c. as well as to my recent on-line reviews of Finnegans Wake by James Joyce and The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath by H.P. Lovecraft. And more.

And to the intriguingly obsessive use of a semi-colon followed without a space by an em dash. As well as elongated em dashes and other typographical idiosyncrasies.

MY REAL-TIME REVIEW WILL TAKE PLACE IN THE COMMENT STREAM BELOW AS AND WHEN I HAPPEN, IF AT ALL, TO RE-READ THIS BOOK:-

BOOK I

Chapters I – IV

“I wish either my father or my mother, or indeed both of them, as they were in duty both equally bound to it, had minded what they were about when they begot me; had they duly consider’d how much depended upon what they were then doing;—”

“But alas! continued he, shaking his head a second time, and wiping away a tear which was trickling down his cheeks, My Tristram’s misfortunes began nine months before ever he came into the world.”

I suspect we won’t get to the narrator Tristram’s actual birth till much later in the book, indeed the book might finish before he begins! But each of these chapters are homunculi as small as the HOMUNCULUS of our future hero inside the belly of his mother…and as annoying as his father’s sciatica, shooting down the leg of pain that is this text. A text both painful and hilarious.

“Pray my Dear, quoth my mother, have you not forgot to wind up the clock?—Good G..! cried my father, making an exclamation, but taking care to moderate his voice at the same time,—Did ever woman, since the creation of the world, interrupt a man with such a silly question?”

“To my uncle Mr. Toby Shandy do I stand indebted for the preceding anecdote,…“

Chapter V

I am not going to make a habit of quoting large chunks of this book as I wend my way through it, but this bit below seems vital to my pre-thesis of AntiNatalism embedded within it (a moment of pre-Birth retrocausality?):-

“On the fifth day of November, 1718, which to the aera fixed on, was as near nine calendar months as any husband could in reason have expected,—was I Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, brought forth into this scurvy and disastrous world of ours.—I wish I had been born in the Moon, or in any of the planets, (except Jupiter or Saturn, because I never could bear cold weather) for it could not well have fared worse with me in any of them (though I will not answer for Venus) than it has in this vile, dirty planet of ours,—which, o’ my conscience, with reverence be it spoken, I take to be made up of the shreds and clippings of the rest;—not but the planet is well enough, provided a man could be born in it to a great title or to a great estate; or could any how contrive to be called up to public charges, and employments of dignity or power;—but that is not my case;—and therefore every man will speak of the fair as his own market has gone in it;—for which cause I affirm it over again to be one of the vilest worlds that ever was made;—–“

Chapter VI

The Tristram Narrator – who is not yet born in the formal time-line of the novel – now seeks collusion with you the reader; in fact he is trying explicitly to ‘groom’ you as some do on the Internet these days, but this grooming or collusion is coupled with retraction of some details: a tantalising combination of openness and obliquity: even an opacity, for the transcendence of which you shall no doubt require, as in ‘Finnegans Wake’, captcha codes or passwords.

Chapters VII – X

“Nor does it much disturb my rest, when I see such great Lords and tall Personages as hereafter follow;—such, for instance, as my Lord A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, and so on, all of a row, mounted upon their several horses,—”

And there is talk of HOBBY-HORSES, too, amid the digressive story of a midwife. But first Parson Yorick…

A timely warning. I am a hobby horse sort of reviewer, as you may have guessed. This book has now become my latest HOBBY-HORSE as will become its leitmotifs that I shall inevitably attempt to mould into a gestalt. A book that possibly uses from within itself the same as what I am about to do to it, with my falsely moulding it, grooming it…?

An important aside:

After due investigation, I seem to be the only person in the world to have noticed, in connection with the above ‘Tristram Shandy’ quote, that Mr Ramsay in Virginia Woolf’s ‘To The Lighthouse’ always foundered on getting past Q in the alphabet!

I have no time today for further reading of this book. Hopefully more tomorrow. But I notice the above ‘design’ appears within the next few pages of text.

Meanwhile, I have been thinking over night, too, about this book, one that seems to be the pioneer of the experimental non-linear novel – not necessarily an anti-novel, but certainly the Pierrot Lunaire of its day. I sense so far that the Tristram narrator is using this non-linearity of his own delayed life as a means to avoid the captcha ‘captivity’ (see my recent review of ‘Finnegans Wake’) of an unwanted or unasked for life (a variation upon which was described in my one and only novel, a passage quoted here)…

Chapters XI and XII

I have alerted the various on-line forums I attend about this my on-going review of the Sterne book with this pointer: “Tristram Shandy as a Ligottian Anti-Natalist novel as well as an Anti-Novel per se?” Indeed, there is a Ligottus knot at least to untie here. Or many ligotti. The question will not be answered simply, as one can never account properly for irony, but based purely on nothing but the text, whether the Parson Yorick character is meant to represent a cheery Sterne himself or just another side of Sterne, the Intentional Fallacy will not give us enough rope to hang ourselves. The character of Parson Yorick in these two chapters lives cheerily and dies in distress to become that skull of Yorick in Shakespeare’s Hamlet or the black block you see above representing endless death after pain (although this character is due to appear later, I recall, in this non-linear novel – a bodytrap, indeed!) Connections also with Cervantes’ Don Quixote and Burton’s ANATOMY of MELANCHOLY. More grooming of you the reader in these two chapters, too. Grooming you for what, though?

Chapters XIII – XVII

“;—-which, betwixt you and me, and in spite of all the gentleman-reviewers in Great Britain,…”

Cut his face to spite his nose!

You know, Schopenhauer was verifiably a fan of ‘Tristram Shandy’…

Meanwhile, Sterne plagiarised passages from Robert Burton et al in this novel and passed them off as his own. But it’s the way he does it that makes this book a work of genius.

And to digress further, you would die a thousand deaths rather than have to re-read the full legal document in this section of the book concerning his mother’s confinement, I guess.

Chapters XVIII and XIX

I simply have to quote this whole passage about Tristram’s father who felt that the actual names given to people carried their character as well as fate, and his father ended up, by some quirk of his own character and fate, calling his son (the narrator currently grooming you) by a name that carried the worst possible weight in this regard:

“But of all names in the universe he had the most unconquerable aversion for Tristram;—he had the lowest and most contemptible opinion of it of any thing in the world,—thinking it could possibly produce nothing in rerum natura, but what was extremely mean and pitiful: So that in the midst of a dispute on the subject, in which, by the bye, he was frequently involved,—he would sometimes break off in a sudden and spirited Epiphonema, or rather Erotesis, raised a third, and sometimes a full fifth above the key of the discourse,—and demand it categorically of his antagonist, Whether he would take upon him to say, he had ever remembered,—whether he had ever read,—or even whether he had ever heard tell of a man, called Tristram, performing any thing great or worth recording?—No,—he would say,—Tristram!—The thing is impossible.

What could be wanting in my father but to have wrote a book to publish this notion of his to the world? Little boots it to the subtle speculatist to stand single in his opinions,—unless he gives them proper vent:—It was the identical thing which my father did:—for in the year sixteen, which was two years before I was born, he was at the pains of writing an express Dissertation simply upon the word Tristram,—shewing the world, with great candour and modesty, the grounds of his great abhorrence to the name.

When this story is compared with the title-page,—Will not the gentle reader pity my father from his soul?—to see an orderly and well-disposed gentleman, who tho’ singular,—yet inoffensive in his notions,—so played upon in them by cross purposes;—to look down upon the stage, and see him baffled and overthrown in all his little systems and wishes; to behold a train of events perpetually falling out against him, and in so critical and cruel a way, as if they had purposedly been plann’d and pointed against him, merely to insult his speculations.—In a word, to behold such a one, in his old age, ill-fitted for troubles, ten times in a day suffering sorrow;—ten times in a day calling the child of his prayers Tristram!—Melancholy dissyllable of sound! which, to his ears, was unison to Nincompoop, and every name vituperative under heaven.—By his ashes! I swear it,—if ever malignant spirit took pleasure, or busied itself in traversing the purposes of mortal man,—it must have been here;—and if it was not necessary I should be born before I was christened, I would this moment give the reader an account of it.”

Chapters XX and XXI

The Tristram Narrator tells one of you more inattentive readers to go back and read the whole of the previous chapter again – in case its moral got lost at the bottom of the ink horn. Whether baptism should precede or follow birth. I should think it should follow death, myself, to obviate any onward course into nothingness! Not that baptism works WHENEVER it is used.

And there follows a portrait of good-natured Uncle Toby from whom, one gathers, our Tristram gets most of his own pre-birth information, including the recurrent row between this uncle and his father about the concupiscent disgrace of one of their sisters in retrograde with Copernicus,..

Anyway we now learn about the coming of the Internet where eventually this novel will become better known by this my review you are now reading:

“When that happens, it is to be hoped, it will put an end to all kind of writings whatsoever;—the want of all kind of writing will put an end to all kind of reading;—and that in time, As war begets poverty; poverty peace,—must, in course, put an end to all kind of knowledge,—and then—we shall have all to begin over again; or, in other words, be exactly where we started.”

Chapter XXII

“In a word, my work is digressive, and it is progressive too,—-and at the same time.”

A very important statement, possibly central to the whole book, a book that proceeds, regresses, stops, stutters and starts again and diverts again until we’re back on track – or are we? It is as if Sterne sternly fixes upon sex and regeneration as a necessary ‘coitus interruptus’ or a bashfulness to complete the act with a woman or complete the narration, an obsessive fixity so as to avoid death and to avoid procreating others who would otherwise have to face a ‘life interruptus’, the pain of foreseen and actual death. A Perpetual Autumn?

From my first reading of it in the 1960s, I seem vaguely to recall later in this book there are scenes explicitly demonstrating such considerations. Or was that my own youthful fear – a fear of breaking some envisaged sex barrier for the first time – that made me imagine such scenes? Imagined by me then or imagined by me now about me then? We shall see.

BTW, this earlier quote at the outset of this review – “Pray my Dear, quoth my mother, have you not forgot to wind up the clock?—Good G..! cried my father, making an exclamation, but taking care to moderate his voice at the same time,—Did ever woman, since the creation of the world, interrupt a man with such a silly question?” – is the most famous coitus interruptus in all literature…and now seen with that vital other ingredient in Time’s danger of itself stopping.

This review will now continue in the comment stream HERE

Alternatively continued here part by part:

http://weirdmonger.livejournal.com/283828.html

http://weirdmonger.livejournal.com/284992.html

http://weirdmonger.livejournal.com/285339.html

http://weirdmonger.livejournal.com/285606.html

http://weirdmonger.livejournal.com/285742.html

http://weirdmonger.livejournal.com/286414.html

http://weirdmonger.livejournal.com/286534.html

The links to the eight parts of the Tristram Shandy real-time review:

https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2014/03/15/tristram-shandy/ (this one)

Reblogged this on THE DREAMCATCHER OF BOOKS: Gestalt Real-Time Reviews.