THE MONK’S BIBLE

By Harold Billings

Photo by Zagava

Les Éditions de L’Oubli MMXIV

Previous ‘Les Éditions de L’Oubli’ in the modern age are shown here.

Previous reviews of all my purchased Zagava – Ex Occidente books are linked from here.

I shall report on my experience of this book in the comment stream below as and when I happen to read it.

It is a highly luxurious book, with 48 pages. “Limited to 100 numbered copies for sale, plus extra copies, which are reserved for private distribution.” Mine is numbered 10.

“…but it will take me awhile to learn the names of this vast torrent of flowers and foliage. […] A recent heavy rain came and the stream burst its banks…”

This short story, as owl- or para-quel to A DEAD CHURCH, is wholly readable as a separate entity, with a plotted ‘envelope’ of a modern couple reading it as the commissioned translation of the marginalia in an ancient Bavarian Bible, transported, in the dark past of the earlier pre-quel, to the new world by migrants, a man and his gradually blind son and wife, leaving their daughters behind with their own imputed happy ending as our own modern couple in the ‘envelope’ may be forced to endure their own imputed happiness forever?

The meat of this book, though, is the passage across the ocean in an old ship, and, later, the formation of the old church and its later downfall, by torrenting stream of both a flood of local superstition and a flooding out of the graveyard, fearing, as they passage across the oceans, even hoping, that their linked Bavarian ghosts and angels travel with them, including the blind son’s familiar …well, I can only tell you so much! Like the marginalist’s vision of his dead wife’s face as recurrent faces on such fleeting flying things, and like his fear for his blind son’s sexual health, and like much more.

There is a definite feeling in me about this short story being substantial enough to form this thick-papered tome, one with its luxuriant stiffening and hedonist artistic context, ensuring we realise that the words are far more weighty and fateful and downright horrifying as they would be if they were, say, scribbled in its margins, more easily outlasting in meaning and physical survival most other books in this fragile world. But, believe me, the marginalist’s failure, in this book, to knot a ‘nostril link’ (something that I advisedly call a ‘ligottus’) is probably the centre of this whole growing mythology of the angel bird, this stiffening monumentality of happenstance, and other matters of which perhaps even the book’s headlease author may not realise the implications?

Whatever your thoughts on its presentation, this is the genuine opening out or forced lifting of the lid of a weird fiction story that deserves the attention of those with the interest in such things and with the fortitude to withstand its implicatory monumentality as a classically disturbing, arguably anti-natalist, literary work.

end

I have forgotten my exaggerated anti-natalist response!

I cannot understand how anyone reading the final paragraph in this story could begin to conceive of the work as antinatalist.

I felt the last paragraph was ironic. But whatever that particular interpretation within the scope of Wimsatt’s intentional fallacy, this is a brilliant work that will stay with me. 🙂

Thanks for commenting, Harold.

Des

I took this photo today with such an angel bird following me on my regular morning walk by the seafront near where I live:

It also roosted on the building below along the way but you can’t see it so clearly;

Des, the demise of that creature has not yet been reported. I can only believe that it has discovered your location through your comments on the books that describe some of its fate. I cannot control it, only report on its activities after the fact. I am convinced that it plans on attending the birth of the first child of Susan’s. Perhaps that may ultimately distract it from you. As was reported in The King in Yellow many years ago, we can only turn now to God.

Des, you may be aware that there was a change made in that line in the British edition from the first American. As I recall, subsequent American editions followed the change first made in the British edition. Best, Harold

Thanks, Harold. I didn’t know that.

To mark our exchanges on this review, I have tonight read aloud the whole of ‘The Yellow Sign’ here: http://www.filefactory.com/file/5fjnwwrvrqkj/VN650649.WMA

For the unknowing, the first edition reads “… there was only Christ to cry to now.” while the British edition and subsequent American editions read “… there was only God to cry to now.” Why lose the wonderful alliteration to move from the specific lord to the more general one? What philosophical or religious motive moved Chambers to make this change? There has never been an answer.

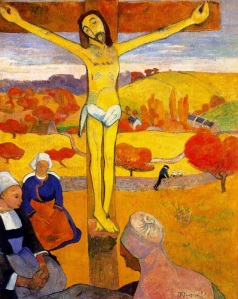

THE YELLOW CHRIST by Paul Gauguin (1889)

Showing, gathered in prayer, Breton women in Northern France.

I have decided to start a real-time review of a re-reading of THE KING IN YELLOW as a whole, here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2014/10/31/the-king-in-yellow-a-real-time-review/

The Angel Bird followed me again today: http://nullimmortalis.wordpress.com/2014/11/01/and-the-angel-bird-at-clacton-pier-this-morning/

I am glad you have this knack, since there are frequently extremely thoughtful reviews by you of the best in new fiction and various other enchantments that you throw into your comments. Just your comments themselves are occasionally as good as the new publications you review.

Rather than just three Breton women, they would be, according to St. John: “Now there stood by the cross of Jesus his mother, and his mother’s sister, Mary the wife of Cleophas, and Mary Magdalene.” Surely, Gauguin meant to paint the entire scene?

This book cross-referenced with the angel Peacock here: https://dflewisreviews.wordpress.com/2017/05/10/ornithology-sixteen-short-stories-by-nicholas-royle/#comment-9849